欢迎来到 阳泉市某某投资咨询有限责任公司

全国咨询热线: 020-123456789

联系我们

Gov't in dilemma over North Korea restaurant defectors

来源:阳泉市某某投资咨询有限责任公司 更新时间:2024-10-30 10:25:26

|

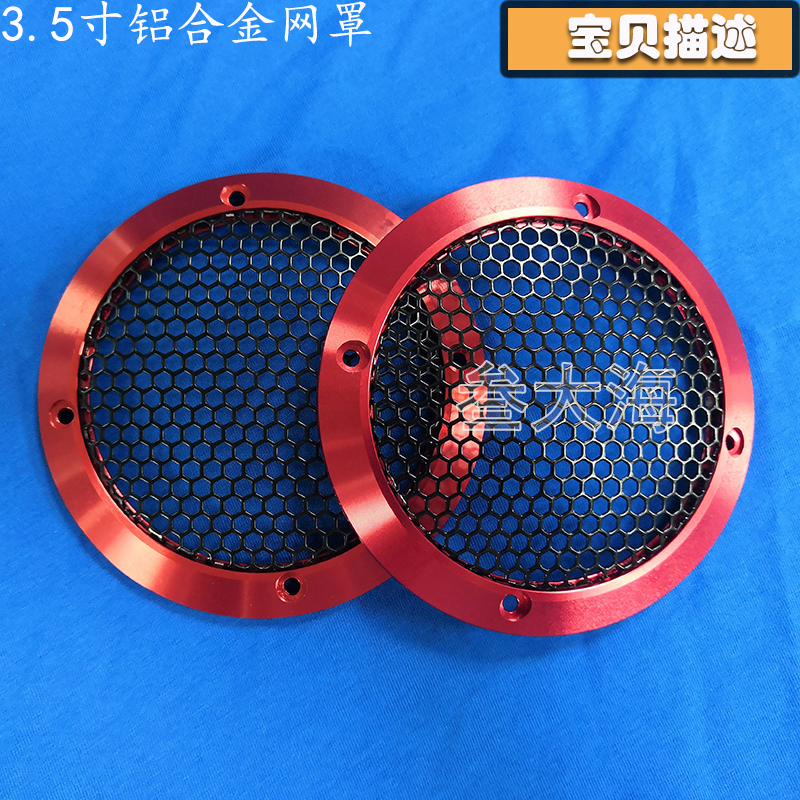

| Twelve North Korean restaurant workers and their manager arrive at Incheon International Airport on April 8, 2016. / Korea Times file |

By Park Ji-won

The South Korean government has been caught in a dilemma dealing with the former workers of a North Korean restaurant in China who allegedly defected to the South in 2016, following a series of new testimonies from them that the group defection was orchestrated by the South's spy agency.

South Korean activist lawyers and the U.N. special rapporteur have been urging the government to start a fact-finding process, while the Moon Jae-in administration, amid the mood of reconciliation between the two Koreas, is maintaining the position that they defected to the South voluntarily.

Ho Kang-il, the manager of the restaurant in the Chinese port city of Ningbo, told the Yonhap News Agency Sunday that he was threatened by South Korea's National Intelligence Service (NIS) to defect together with other workers there, or otherwise it would inform the North that he had been cooperative with the NIS.

"They threatened that unless I come to the South with the employees, they would divulge to the North Korean Embassy that I had cooperated with the NIS," Ho said. "I had no choice but to do what they told me to."

Ho insisted many of the employees followed him without understanding where they were actually going because Ho told them they would work for a restaurant in a Southeast Asian country. Ho said they learned they were going to the South after boarding a plane.

According to Ho, the NIS promised to help him obtain South Korean citizenship and run a restaurant in Southeast Asia but it did not keep the promise. He said he and some of the workers want to return to the North.

In April 2016, the then Park Geun-hye government announced that the 12 young women and their manager defected to South Korea of their free will in the largest group defection since 2011 when North Korean leader Kim Jong-un took power.

It was unusual for the government to publicly announce the defection due to security reasons, and their defection process was unusually swift. The workers entered the South via Malaysia, a route that was seen as impossible without some kind of government-level assistance.

So suspicions emerged that the spy agency was involved in the defection, with some rights groups, including the Lawyers for a Democratic Society, claiming it was an "abduction" by the NIS. They said the Park administration attempted to consolidate conservatives ahead of a general election, which was held only days after their defection was made public.

Ho's interview was in line with the announcement by the U.N. special rapporteur on North Korea's human rights situation, who called for a thorough investigation on their issues last week.

Tomas Ojea Quintana, the rapporteur, said, after meeting with some of those employees, that some of them did not know where they were being taken when they were brought to South Korea. "It's clear there were some shortcomings about how they were brought to South Korea," he said.

Quintana added that if they were actually abducted, it would be a "crime," calling for a "thorough and independent" investigation, and punishment of those held responsible.

Pyongyang has demanded their return, saying they were abducted by the South Korean intelligence agency.

However, the unification ministry has repeated the previous stance that those defectors came to Seoul of their own volition, even after the rapporteur's request.

Even if the manager's claim is true and some want to go back to the North, it will be difficult for the Moon administration to return them as it is apparently admitting that the government committed a serious crime, even though it was conducted by the former administration.

Focusing on the issue may also deal a blow to the current reconciliatory mood between the two Koreas and the ongoing denuclearization talks.

But calls are rising that the government at least needs to initiate a fact-finding investigation into the allegation.

城市分站

友情链接

GG扑克注册 GGPoker GG扑克 GGpoker注册 GG扑克注册 GG扑克下载 GGpoker官网 GG扑克注册 GG扑克注册 GGpoker下载 GGpoker注册 GGpoker注册 GG扑克官网 GG扑克下载 GGPoker GGpoker下载 GG扑克注册 GG扑克官网 GG扑克下载 GG扑克下载 GGpoker注册 GG扑克官网 GGpoker下载 GGpoker下载 GGPoker GGPoker GGpoker下载 GGpoker下载 GGpoker注册 GG扑克 GG扑克官网 GG扑克下载 GG扑克 GG扑克 GG扑克下载 GG扑克官网 GG扑克官网 GGpoker官网 GGPoker GG扑克 GGpoker官网 GGpoker注册 GG扑克注册 GGpoker官网 GG扑克 GGPoker GGpoker官网 GGpoker官网

联系我们

Copyright © 2024 Powered by 阳泉市某某投资咨询有限责任公司 sitemap